This website provide easily accessible information about the structure and working practices of local government in England.

It builds on - and adds up-to-date comment, analysis and information to - the NAO's 2017 Guide to Local Authorities.

The systems and patterns of local government are not consistent across the UK. The devolution arrangements for to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland differ between themselves as well as being fundamentally different from the pattern in England. This website currently describes local government in England. There is, in the other countries, a closer relationship between national and local government policy, funding and practice than that existing in England. Examples are around education, (especially educational funding and control), police and Fire and emergency services, aspects of health and social care, special planning, economic development and environmental management.

Structure and Organisation

There are four main types of local authority, though there are marked differences within each typology.

- County Councils

- District and Borough councils,

- Metropolitan Councils

- London Boroughs

There is a lower tier in more rural areas:- Parish and Town Councils

Follow this link for further detail.

Council Services

As with other aspects of local government in the UK it is misleading to offer too many generalisations but ...

- for most County local authorities, their primary services are social care:- both adults' and children’s.

- for District and Borough councils, their most prominent and visible services are leisure and housing (though few have residual landlord services today). But their other key role is ‘planning the built environment’.

The Local Government Association publish regular polls summarising residents' satisfaction with the quality etc. of the services provided by their local councils. A 2020 poll is here and others can be accessed via the LGA website.

How is Local Government Financed?

Local authorities receive money from central government and raise money locally, mainly through taxes and charges. The relationship with, and funding from, central government is described in a separate section below. This section of the website focusses on the fundamental issue of the ability of the council (local authority) to raise taxes to pay for local services.

Perhaps the key point to remember is that England is one of the most centralised nations in the OECD. Regional and local taxes amount to only 1.7% of GDP. This concentrates an extraordinary degree of power in the hands of a small number of government ministers and distances decision makers from the complexities of the challenges and opportunities that vary so much from one place to another. No-one thinks this is a great place to be, but no-one seems to know how to get out of it.

These separate web pages provide information about:

- Local taxation in an historical context – why we have it and what purposes does it serve?

- The budget setting process

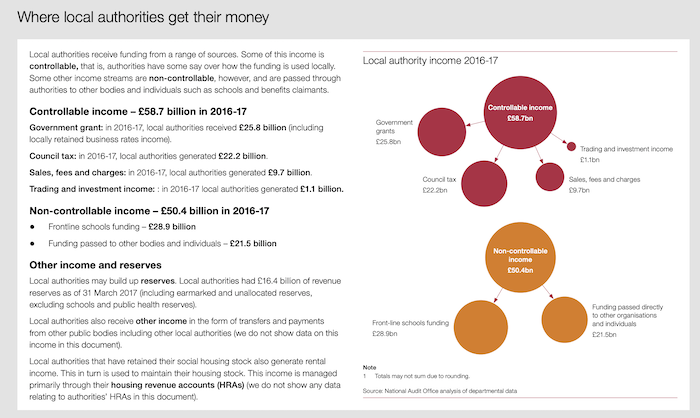

Here is a useful summary of sources of local authority funds in 2016-17. (Click image to enlarge.)

As noted below, central government has slashed central funding of local council expenditure. Some councils have as a result been tempted (or were forced?) to enter into commercial (including property and financial) investments in order to bolster their income. But higher income from investments is inevitable associated with greater risk and these attempts to chase high returns all too often end in tears as the counterparties are generally much more knowledgeable and professional than local authority staff.

- Both Northamptonshire (in 2018) and Croydon (in 2020) were amongst the first councils to be forced to issue Section 114 notices (in affect announcing their bankruptcy) which in turn forced them into even more severe spending cuts.

- Woking Council, with an annual revenue of around £16m, was allowed to build up debts of £1.8 billion. The Times reported:-

-

Woking and Singapore do not, on the face of it, have much in common. One is a sleepy commuter town in England’s stockbroker belt, the other a bustling city state in Asia. But one man’s ambition to turn Woking into the “Singapore of Surrey” sowed the seeds for probably the most spectacular financial collapse ever to hit a local authority. Almost ten years ago, Ray Morgan, then the chief executive of Woking borough council, stood in front of local business leaders holding a picture of Singapore and announced: “We want Woking to become a city. We are looking to be Surrey’s economic hub.”To his somewhat bemused audience, he then compared the waters of the Singapore Strait to the Basingstoke Canal.

The biggest single disaster, amid myriad smaller disasters, was the money the council ploughed into the Victoria Square redevelopment in the town centre. This plan, first conceived under Morgan’s leadership in 2012, was to build a 34-storey complex containing residential apartments, a Hilton Hotel, 125,000 sq ft of commercial space anchored by a Marks & Spencer, a multi-storey car park, medical centre and two public plazas. All of the money Woking used to pay for the project was borrowed — mostly from the central government, which told The Times in 2017 when we raised the alarm about reckless council spending that there were “strong checks and balances” in place to protect taxpayers’ cash. Fast forward to this year, and the value of the Victoria Square site was downgraded by nearly half a billion pounds to just £199 million, with the council still struggling to fill all the retail units. In effect, the Treasury’s huge loans to Woking now have no collateral to back them up and the council cannot afford the interest. - Then, in 2023, "A series of catastrophic business deals ... have left Thurrock Council with [a] funding gap three times the size of its annual budget and the largest ever faced by a local authority". "Over a period of five years the council recklessly gambled with £1bn borrowed from other local authorities, repeatedly ignored warnings about the risks involved and then failed to disclose when investments had lost millions of pounds." "The Council secretly handed £655m to a local businessman. He spent the money on a private jet, a yacht, a 232 acre mansion, a Bugatti, and loads of other stuff. Then he wound up the company." The formal Thurrock report is here.

- The city of Nottingham declared itself bankrupt towards the end of 2023 having lost £38m on an energy company that it had itself set up.

The NAO reported in 2025 that local government finances were becoming unsustainable, due to increasing demand on essential frontline services, the impact of delayed finance reform, and the erosion of investment in preventative programmes.

Audit

The Government probably made a big mistake when it abolished District Auditors and the Audit Commission around 2015. Their absence may in particular have facilitated the bankruptcies mentioned above. Woking (see above) did not have a completed external audit between 2018 and early 2023.

The creation of the Office for Local Government (announced in 2023) did not seem likely to make much difference as its role is mainly information gathering and dissemination with the aim of facilitating benchmarking and promoting best practice.

The Relationship with Central Government

There are three overlapping aspects to this key relationship.

- The first is the extent to which power and responsibilities are in principle delegated from central to regional and local government.

- The second is the flow of money from central to local government.

- The third is the political relationship - including the extent to which central government allows local authorities to take controversial local initiatives - and in particular to fund them (and top up central government funding) by raising local taxes.

Regional Government

The UK suffers from its failure to resolve the debate between those who want to organise regional and local government around economic entities and those who are (understandably) attached to civil entities: the cities and counties with which we are all familiar. It makes little economic or organisational sense, of instance, for Newcastle and Gateshead to be governed separately, but it makes a lot of emotional sense if you live in one or the other.

The UK suffers from its failure to resolve the debate between those who want to organise regional and local government around economic entities and those who are (understandably) attached to civil entities: the cities and counties with which we are all familiar. It makes little economic or organisational sense, of instance, for Newcastle and Gateshead to be governed separately, but it makes a lot of emotional sense if you live in one or the other.

The 1969 Redcliffe-Maud Report report recommended the abolition of all the existing county, county borough, borough, urban district and rural district councils, which had been created at the end of the 19th century, and replacing them with new unitary authorities. These new unitary authorities were largely based on major towns, which acted as regional employment, commercial, social and recreational centres and took into account local transport infrastructure and travel patterns. There were to be 58 new unitary authorities and three metropolitan areas (Merseyside, South East Lancashire/North East Cheshire or 'Selnec' and West Midlands), which were to be sub-divided into lower tier metropolitan districts. These new authorities, along with Greater London were to be grouped into eight regions, each with its own regional council. But no government has since felt able to implement Redcliffe-Maud's recommendations.

There was an interesting dissenting report by Derek Senior, recommending the creation of French-style provinces - see map to the left. You can click on it to see a larger version.

Government Offices for the English Regions were established in 1994. Until 2011, when they were abolished, they were the primary means by which a wide range of national policies and programmes were delivered in the regions of England.

Follow this link to read David Higham's fascinating 'lessons learned' analysis and history of Government Offices. But others were less keen on GOs, arguing that Whitehall departments' regional offices generally worked well together, and the the imposition of GOs reduced their collective impact, not least because appointment as Regional Director was never a good career move for an ambitious Mandarin, who may have felt little emotional connection with 'their' region and probably felt greater loyalty to their head office in London.

The absence of strong regional entities, together with the financial weakening of local government (see below) may well have been a factor in the weaknesses in the government's response to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic - see for instance the Manchester Evening News report No Way to Run a Country.

In 2021, over 50 years since Redcliffe Maud, , David Higham argued that 'All in all, it is hard to identify any real progress since 1969 when Harold Wilson said, in reference to the Redcliffe Maud report, “It is my hope that the reorganisation of local government will provide an opportunity and the incentive …..for a fresh attack on (this) problem of central financial control”.' His blog is here.

The House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee returned to the question in 2022, noting that "The current state of the governance arrangements for England is a significant and pressing problem that has been neglected by successive Governments for too long. There is an urgent need for significant reform to the way that England is governed. It is important that governance arrangements are established that not only work effectively, but that can be seen to work effectively, in order to strengthen and restore public trust in the functioning of our democracy at all levels." Their report, 'Governing England', is here.

Published a few weeks later, the 2022 Brown Commission Report for the Labour Party (A New Britain: Renewing our Democracy and Rebuilding our Economy Report of the Commission on the UK’s Future) may or may not turn out to be influential. The IfG's Hannah White commented as follows:

Many might see constitutional and economic questions as entirely separate, but the Brown commission motivates its constitutional recommendations by pointing to economic failings – stagnant productivity growth for the last decade and large geographic inequalities that have persisted for far longer. It argues that economic failings in England in particular are at least partly a result of a constitutional settlement that is not working with powers too centralised and local government too weak. In this, and on its proposals for civil service reform, the Commission shares much of its diagnosis with the Conservative government, raising the possibility of bipartisan agreement on priorities.

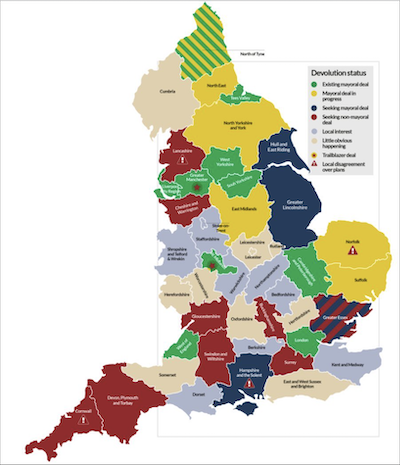

The above map (which will expand if you click on it) shows the extent and variety of devolution from central government as at July 2023.

Follow this link to read a short note by David Higham - The Challenge of Levelling Up Economic Decision-Making.

The Financial Relationship

Government funding for local authorities fell by around 50% in real terms from 2010-11 to 2017-18. This was the equivalent of a 28% real-terms reduction in ‘spending power’ (government funding and council tax). Follow this link for further detail and debate.

The Political Relationship

There are arguments both for and against the limitations that are placed upon the powers that local government has by central government.

One view is that left wing councils' powers to tax or acquire assets needs to be restrained by central government to avoid raising taxes beyond that which central government deems to be reasonable or line with overall public borrowing. Equally, many right wing councils need to be forced to spend money on what were in earlier times seen as the undeserving poor.

- There were some tremendous battles in the 1980s between Mrs Thatcher's Conservative Government and several left wing local authorities - with devastating consequences for some local residents.

- When Labour's John Prescott removed the central ring fence around Sure Start, some councils create only a bare minimum of children's services.

- When the Cameron government gave responsibility for public health to local councils, some spent the money on filling in potholes in roads (popular with motorists) rather than tackling drug addiction, out of bogus concern for preventing road accidents.

The other view is that local authorities know best what local people want and should have powers that enable them to deliver. Clearly when strong political influences are at play there have been times when central government has perceived this to be a direct challenge to the overall authority of central government. This does introduce the issue of the role of local political policy, for most councillors are elected as representatives of formal political parties and there will be political pressure for councils with a working majority to have policies that reflect the national policies of that party.

Current Issues

The Institute for Government published an excellent English Devolution Explainer in 2023.

Follow this link to read Ian Briggs' summary of a number of contentious issues that were causing concern in 2020.

Britain's (insane?) centralisation reached a new low in 2023 when the Sunak government published a prospectus inviting local authorities to register their interest in being provided with £2,500 chess sets (a chess table and four seats) to be placed in local parks.

How Decisions Are Made

Here, again, we are looking at a system that has many variations and approaches. The notion of a separation of powers between the elected and those who are employed much like most central government systems can be found in UK local government. A common myth is that those who are employed within UK local government are ‘civil servants. They are in fact technically employed by the elected councillors and not the UK or devolved Governments.

- Follow this link for a fuller description of the many different types of UK public servant.

- Information about the numbers employed by local authorities will be added shortly.

In most respects the decisions that are made by local authorities that impact upon local people are made by the councillors. However, there are processes of delegations that allow the employees (referred to as officers) to make decisions within the boundaries of policies and procedures that are laid down and are transparent and contained within local constitutional arrangements. A council’s constitution has both certain flexibilities and other legal compliances. The compliances are laid down within Acts of Parliament, some being specifically related to local government, others related to other forms of regulation affecting more than local government.

The decision making process can go wrong, and can go badly wrong when both councillors and their officers fail to respond appropriately when their errors are pointed out. The Sheffield street trees controversy was a classic of this nature and it is well worth reading at least the first few pages of Sir Mark Lowcock's detailed report into what had gone wrong. The local press noted that the "city council had twice misled the high court during the fierce row, during which elderly residents were arrested when trying to protect trees from the chainsaws. During one particularly contentious episode ... contractors began work at 4.45am, dragging residents out of bed to move their cars before protesters arrived."

Councillors, Voters and the Public

For decades, all local councils have wrestled with the issues of public engagement.

As an example, we only have to look at the data on turnout at local elections. Political scientists have long researched the reasons why people vote, and the policies of national parties can and do have a significant impact on local elections despite the presence of local manifestos of parties. Where there is dissatisfaction with the actions of government this influence is carried through to local issues. In the UK as a whole, generally the turnout at local elections is much lower than in general elections. Even in certain localities that are seen to be highly political active, turnout in local elections can be significantly less. The conclusion that is often drawn that the public are less concerned with the election of their councils than they are of the parliament.

There are ‘hot spots’ where contentious issues prevail, the closure of hospitals being a prime example. Where people feel that any service to the public is less than satisfactory then this can be played through to local elections but it remains an issue for local government to press the credentials for democratic representation at the local level.

When councils seek the opinion of residents about the quality of services they receive by and large the opinion is good, as an example a key issue for local councils is the collection of household waste. Although there are certainly huge variations in the quality and reliability of the service from one place to another most people consistently report positive levels of satisfaction. However, to complicate matters, it is not uncommon for residents to feel that nationally the quality of service is poor, but they feel ‘lucky’ that where they live, they have a good service.

Another litmus test of how the resident feels about local government is the struggle that political parties can have in encouraging people to stand for election, Clearly, it is important for local government to have those who sit in control of local services to be representative of the local population, yet an investigation into the data on the age range of councillors clearly points to the overwhelming predominance of older people standing.

When residents are asked if they are receiving value for money in respect of their payments of council tax then again evidence suggest that councils have some distance to go in proving that they are spending in a prudent and economical manner. In part this may be due to the absence of any meaningful reform of the system. (The amount of tax that residents pay is based upon an imprecise system of value of property.) But other factors include the reporting of the national and local media on council spending and a challenge that councils have in effectively communicating what their priorities are.

Jonathan Myerson wrote an entertaining and informative description ( Stranger than Fiction ) of his time as a Councillor in the London Borough of Lambeth between 2002 and 2006.

And Matthew Engel's New Statesman report ( The Reluctant Politician ) of his appointment as a Councillor in Herefordshire is equally entertaining and informative.

A Little History

The House of Common Library has published an excellent History of local government in English towns and cities.

Local government - and its officers - used to be much more powerful than their modern counterparts. Here is a nice extract from a piece by Sir Rodney Brooke who retired in 1997 having himself spent six decades in local government and who was the last person to invoke the Riot Act.

Here are links to some other interesting information:

Further Reading

Jessica Studdert published the excellent Local Government Explained in 2021.

A sensible next place to look will be the website of the Local Government Association. And Voting Counts offers simple unbiased resources to help you understand local elections, Mayoralties etc.

These three free or inexpensive booklets offer invaluable advice for local government employees and others:-

Further information about my websites, and my contact details, are here.